Last summer I visited the exhibition ‘David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night’, at The Whitney Museum, New York. Although I have a background in art history and consider myself a keen street art observer, I had never heard of the man. I was in for a surprise: the exhibition blew me away and left an indelible impression.

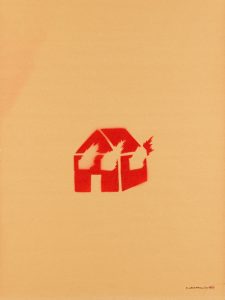

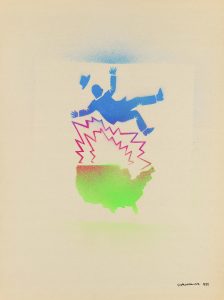

Why is it, I have been wondering, that Wojnarowicz’ work never figures in lists of Street Art classics? His work was thoroughly influenced by Street Art – and once, back in 1979, he was even considered one of the most prominent street artists in the East Village, with his stencilled pictures of burning houses and falling figures.

Well, it’s complicated. Alongside Haring and Basquiat, David played a leading role in the New York Avantgarde of the late 70s and early 80s. He manifested himself as an all-out contemporary, postmodern artist – known for his painting, super-8 films, mixed-media collages, photography, performance art, writing and, of course, his graffiti art and murals. Still, Haring and Basquiat have gone down into history as pioneers of Street Art culture, while Wojnarowicz is neglected. I think this has something to do with the language of his work.

Violant language

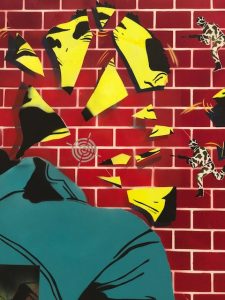

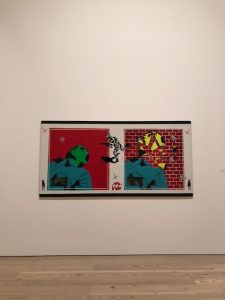

Take a look at his ‘Green head’. This diptych, made with acrylic and spray paint, has all the ingredients of good Street Art: a strong composition, outstanding colors, stencilled figurines, and there is even the suggestion of a wall depicted on the right-hand panel. But in contrast to Haring – whose seemingly upbeat work is of course also about AIDS, sex and violence – Wojnarowicz’ visual language is much harsher. The splintered head, the hunting soldiers, the burning house, warplanes, the ancient hunters, the crosshair of a rifle scope… these are all meant to be disconcerting, up in your face. Compared to Haring’s funny creatures and semantics, which probably never offended any passer-by, David’s paintings are deeply disturbing.

The artist-activist

This rough and direct style has everything to do with David’s past. His entire persona was rooted in misery, and his anger against the American government and his age ran deep. As a child he was abused and exposed to child prostitution, as a teenager he became a street hustler, and even when he broke through as an artist his chances were limited. Then, during the AIDS-epidemic, he lost scores of friends. The fact that AIDS was seen as a ‘gay disease’, and the lack of some kind of relief program or form of education about it, enraged him. The New York City government was not prepared to deal with this health emergency, there was no strategy for AIDS patients and people felt scared, abandoned and left to die. All this transformed Wojnarowicz into an artist-activist, dealing with timeless subjects of sex, spirituality, love and loss politically, and head-on.

History keeps me awake at night

Take his ‘History keeps me awake at night (for Rilo Chmielorz)’, dated 1986. The painting presents a dystopic vision of American life. American currency and bureaucratic emblems are depicted alongside symbols of crime, illusion and chaos. The threatening imagery of the painting go against the seemingly peaceful sleep of the man at the bottom of the painting. Above him, a burly white man points a gun directly at the viewer. Wojnarowicz used acrylic, spray paint, and collaged paper on composition board to visualize this image.

The illness

During his relatively short time as a successful artist (15 years) he documented and illuminated a desperate period of American history: that of the AIDS crisis and the culture wars of the late 1980s and early 1990s. The critical directness of his work – with its social, cultural and political statements – are less pleasant to absorb and therefore appeal less readily to mass audiences. In the catalogue for the exhibition, Julie Ault quotes a conversation wherein the artist is asked, “When you’re making art, it’s like a way of not going to the top of the tower and shooting passers by?” Wojnarowicz replied, “Exactly. It’s identifying the impulse to do that and giving it a different form so that I don’t end up going up to the tower.”

In 1987 Wojnarowicz himself learned that he was HIV-positive. He died of AIDS in 1992. Unfortunately, his enormous artistic talent for painting and collage has been overshadowed by his still controversial attacks on American society.